Washington, DC

Most searches for planets around other stars, also known as exoplanets, focus on Sun-like stars. Those searches have proven successful, turning up more than 400 alien worlds. However, Sun-like stars aren't the only potential homes for planets. New research by astronomers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) and the National Optical Astronomy Observatory (NOAO) confirms that planet formation is a natural by-product of star formation, even around stars much heftier than the Sun.

"We see evidence of planet formation on fast forward," said Xavier Koenig of the CfA, who presented the research in a press conference today at the 215th meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

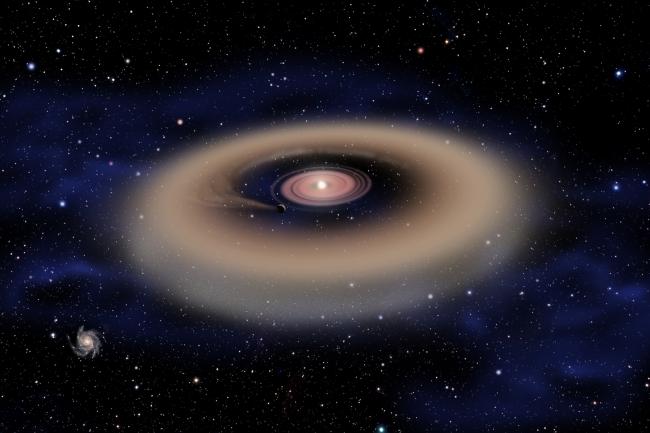

Koenig and his colleagues examined the star-forming region named W5, which lies about 6,500 light-years away in the constellation Cassiopeia. They employed NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope and the ground-based Two Micron All-Sky Survey (2MASS) to look for infrared evidence of dusty planet-forming disks. They targeted over 500 type A and B stars, which are about two to 15 times as massive as the Sun. Sirius and Vega, not included in this study, are two type A stars easily visible to backyard skygazers.

The team found that about one-tenth of the stars examined appear to possess dusty disks. Of those, 15 showed signs of central clearing, which suggests that newborn Jupiter-sized planets are sucking up material.

"The gravity of a Jupiter-sized object could easily clear the inner disk out to a radius of 10 to 20 astronomical units, which is what we see," said Lori Allen of NOAO. (An astronomical unit is the average Earth-Sun distance of 93 million miles.)

Planet formation around A and B stars is a battle between opposing forces. On one hand, the stars' disks tend to be more massive and contain more of the raw materials to build planets. On the other hand, fierce stellar radiation and winds try to destroy the disks rapidly.

The stars in W5 are only about two to five million years old, yet most have already lost the raw materials needed to form planets. This indicates that, at least for type A and B stars, planets must form quickly or not at all.

The prospects for hypothetical alien life are disappointing. The habitable zone, or region where liquid water could exist on a rocky surface, is at a greater distance from the star for A and B stars than for sun-like stars due to their greater luminosity. However, that luminosity comes at the price of a short lifetime. A and B stars live for only about 10 - 500 million years before running out of fuel.

Life existed on Earth for 3.5 billion years in very simple forms, before the Cambrian explosion led to the diversity of life forms we see today. Planets in W5 around these more massive stars wouldn't have that opportunity.

"These stars aren't good targets in the hunt for extraterrestrials," said Koenig, "but they give us a great new way to get a better understanding of planet formation."

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., manages the Spitzer Space Telescope mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington. Science operations are conducted at the Spitzer Science Center at the California Institute of Technology, also in Pasadena. Caltech manages JPL for NASA. For more information about Spitzer, visit http://www.spitzer.caltech.edu/spitzer and http://www.nasa.gov/spitzer.

Headquartered in Cambridge, Mass., the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) is a joint collaboration between the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory and the Harvard College Observatory. CfA scientists, organized into six research divisions, study the origin, evolution and ultimate fate of the universe.

David A. Aguilar

Director of Public Affairs

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

617-495-7462

daguilar@cfa.harvard.edu

Christine Pulliam

Public Affairs Specialist

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

617-495-7463

cpulliam@cfa.harvard.edu