Astrophysicist Sheperd Doeleman Awarded National Academy of Sciences Henry Draper Medal

Sheperd (Shep) Doeleman

Sheperd (Shep) Doeleman, an astrophysicist at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, has been named the recipient of the National Academy of Sciences' 2021 Henry Draper Medal. As founding director of the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), Doeleman is widely known for his pivotal role in capturing the first image of a supermassive black hole in 2019.

This year's Henry Draper Medal recognizes Doeleman's vision and decades-long leadership in developing the instruments and global telescope arrays necessary to produce the world’s first black hole image.

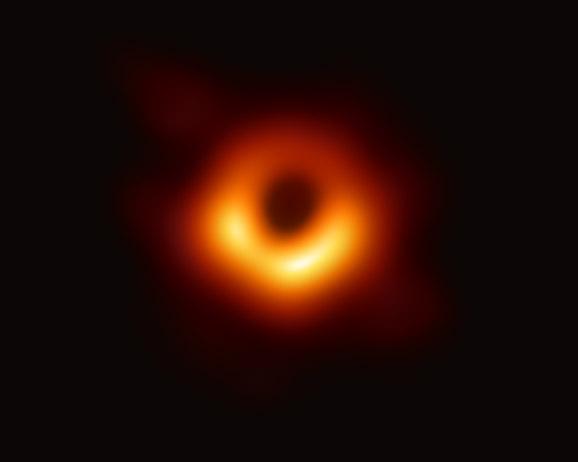

"It's an honor and quite humbling to receive the medal. To bring a black hole into focus has been the central theme of my career, and to capture the image was really a dream fulfilled," Doeleman says. "At the same time, the EHT could not have achieved its goals without the exceptionally hard work and dedication of the entire collaboration. It has been an absolute privilege and joy to work with teams at MIT, the CfA, and across the U.S. and world on this grand scientific adventure. When we saw the telltale 'shadow,' a ring of light bent in the immense gravity of black hole, we were all speechless."

Led by astrophysicist Shep Doeleman, scientists obtained the first image of a black hole in April 2019.

Awarded every four years, the Henry Draper Medal is presented with a $25,000 cash prize. Doeleman will share the award with Heino Falcke of Radboud University.

"There is no more spectacular scientific result than the iconic image of the supermassive black hole in the center of galaxy M87," says Charles Alcock, director of the Center for Astrophysics. "I'd like to extend my sincere congratulations to both Doeleman and Falcke for their greatly deserved recognition with the Henry Draper Medal."

Doeleman's interest in black holes dates back to his graduate student days at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he served as a teaching assistant (TA) to physicist and Nobel laureate Rainer Weiss.

Weiss still recalls Doeleman’s energy and enthusiasm as a TA.

"He was a superb teacher, full of knowledge and whimsy. The students were delighted with him," Weiss says. "If you had a free moment, he would tell you how interesting it might be to actually 'see' a black hole. At the time, he probably didn't realize how to do it, nor how difficult it would be. But he stuck with the idea."

It was at MIT that Doeleman focused on how to improve the bandwidth, sensitivity and magnification power of radio telescopes, which at the time were not powerful enough to image black holes, or even peer into the dark, energy-sucking cores of the galaxies where they live.

Looking back, Doeleman recalls that he was driven by curiosity of the great, mysterious objects, but there was never any assurance of success. “It was a time of great risk. Could we make this work? Could we imagine, design and build the systems and the instrumentation that we needed to do this?"

Spearheaded by Doeleman, the EHT project started as a small group of just 10 to 20 researchers in the 2000s. The hard work paid off in 2008 when Doeleman and his team used their new technology to measure the size of Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole in the center of our Milky Way galaxy. Four years later, the team glimpsed a spinning black hole that powers a cosmic jet of material erupting from the heart of galaxy M87. The success confirmed that visualizing a black hole was both technically and scientifically possible, launching Doeleman on a voyage to capture the first image of one.

By 2017, the EHT had exploded into a massive border-hopping team of more than 300 people, each working at various facilities to build and synchronize a global array of radio dishes that formed a virtual, Earth-sized telescope. The final array was composed of eight observatories, including locations in Hawaii, Chile, Mexico, Arizona, the South Pole and Spain.

"No one knew if the black hole shadow would be observable," says France Cordova, physicist and 14th director of the National Science Foundation. “It took belief and courage on Shep's part to persist with this project and to aggregate a diverse and passionate team, all in the face of funding challenges and doubts on the part of some about whether the objectives could be accomplished."

In April 2019, however, Doeleman’s vision finally became reality when his team unveiled the first direct, visual evidence of a supermassive black hole and its shadow. The image made the front page of hundreds of newspapers around the world and led to some of the world’s most respected scientific awards, including the 2020 Breakthrough Prize in fundamental physics; the American Astronomical Society's 2020 Bruno Rossi Prize; the NSF’s 2019 Diamond Achievement Award; and now, the Henry Draper Medal.

Doeleman and Falcke will be formally presented with the award at the annual meeting of the National Academy of Sciences in April 2021.

"Many people made important contributions to the Event Horizon Telescope," Cordova says. "At the same time, we should recognize the herculean efforts of the pioneer who took risks, both in career and in intellectual focus, to champion and launch a new, extremely technically challenging approach in observational astronomy — with a result that simply astounded the world."

###

Shep Doeleman holds a B.A. from Reed College and a Ph.D. in astrophysics from MIT. Doeleman served as assistant director of the MIT Haystack Observatory prior to joining the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian in 2012, where he is founding director of the EHT. Doeleman is a 2012 Guggenheim Fellow and co-founder of the Harvard Black Hole Initiative — the first center dedicated to the interdisciplinary study of black holes. Funded by a $12.7 million grant from the NSF, Doeleman is currently designing a next-generation Event Horizon Telescope to capture real-time videos of black holes.

About the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian

The Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian is a collaboration between Harvard and the Smithsonian designed to ask—and ultimately answer—humanity's greatest unresolved questions about the nature of the universe. The Center for Astrophysics is headquartered in Cambridge, MA, with research facilities across the U.S. and around the world.

Media Contact:

Nadia Whitehead

Public Affairs Officer

Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian

nadia.whitehead@cfa.harvard.edu

617-721-7371

Related News

Runaway Stars Reveal Hidden Black Hole In Milky Way’s Nearest Neighbor

NASA's Hubble, Chandra Find Supermassive Black Hole Duo

Event Horizon Telescope Makes Highest-Resolution Black Hole Detections from Earth

CfA Celebrates 25 Years with the Chandra X-ray Observatory

CfA Astronomers Help Find Most Distant Galaxy Using James Webb Space Telescope

Astronomers Unveil Strong Magnetic Fields Spiraling at the Edge of Milky Way’s Central Black Hole

Black Hole Fashions Stellar Beads on a String

M87* One Year Later: Proof of a Persistent Black Hole Shadow

Unexpectedly Massive Black Holes Dominate Small Galaxies in the Distant Universe

Unveiling Black Hole Spins Using Polarized Radio Glasses

Projects

AstroAI

DASCH (Digital Access to a Sky Century @ Harvard)

For that reason, the DASCH (Digital Access to a Sky Century @ Harvard) team are working to digitize the plates for digital storage and analysis. The process can also lead to new discoveries in old images, particularly of events that change over time, such as variable stars, novas, or black hole flares.

GMACS

For Scientists

Sensing the Dynamic Universe

SDU Website