Galaxy Clusters

Galaxy clusters are the largest objects in the universe that are held together by their own gravity. They contain hundreds or thousands of galaxies, lots of hot plasma, and a large amount of invisible dark matter. The Perseus Cluster, for example, has more than a thousand galaxies and is one of the most luminous sources of X-rays in the sky. Galaxy clusters are home to the biggest galaxies in the known universe, and provide us with information about the structure of the universe on the largest scales.

Our Work

Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian scientists study many different aspects of galaxy clusters:

-

Mapping the structure of galaxy clusters using the hot plasma that fills the space between galaxies. Even though this plasma’s density is low, its temperature can reach hundreds of millions of degrees, so it shines brightly in X-ray light. The temperature patterns seen NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory reveal a lot about the inner workings of clusters, such as the way gas flows in and out of galaxies.

Astronomers Discover Powerful Cosmic Double Whammy -

Studying how black holes pump energy into the region between galaxies in a cluster, which is known as “feedback”. The feedback process can throttle the formation of new stars inside cluster galaxies, in a complex interaction between the black hole and the hot cluster gas.

Chandra Finds Evidence for Serial Black Hole Eruptions -

Plotting the strange “cold fronts” in the hot gas inside the cluster, which form giant ripples of relatively colder gas. These poorly-understood cold fronts are probably relics of earlier galaxy cluster collisions, and can linger for billions of years.

Scientists Surprised by Relentless Cosmic Cold Front -

Using the South Pole Telescope (SPT) and other observatories to measure the Sunyaev-Zel’dovich effect. These instruments observe galaxy clusters by the fluctuations they create in microwave light from the very early universe. The result is a map of hundreds of galaxy clusters, many of which are too far to be seen directly by the light they emit.

New Cosmological Insights from the South Pole Telescope

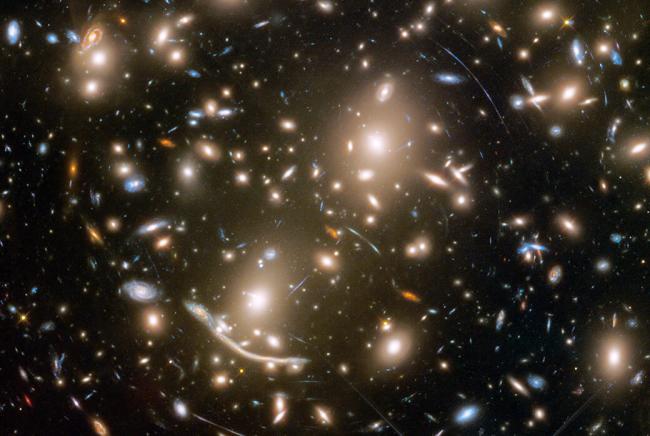

A Recipe for Galaxy Clusters

Even though “galaxy” is right there in the name, galaxies are the smallest of the three ingredients making up a galaxy cluster. The stars and gas in cluster galaxies only make up about 5% of the total mass. Meanwhile, about 80% of the mass in a cluster is in the form of dark matter, which holds everything else together. The huge amount of dark matter in a galaxy cluster produces enough gravity to bend the path of light passing by. That bending, called “gravitational lensing”, turns clusters into giant telescopes, magnifying galaxies that would ordinarily be too faint for us to see. In addition, lensing lets astronomers map where the mass in a galaxy cluster is located.

At 15% of the total, the second most massive contribution to galaxy clusters comes in the form of hot plasma — gas where the electrons have been stripped from their atoms — which fills much of the space between the galaxies. This gas shines brightly in X-ray light, and affects radio light shining through the cluster from more distant sources. As a result, the plasma provides several independent ways to detect and study galaxy clusters.

And finally we have the galaxies themselves, which may weigh in the least, but are still very important. The largest galaxies in the universe live in clusters, and interactions between cluster galaxies are a laboratory for understanding how these huge monsters form. In addition, the galaxies host supermassive black holes, which can have a profound effect on the whole galaxy cluster.

The galaxy cluster Abell 370 contains several hundred galaxies held together by their mutual gravity. The cluster's hot gas and dark matter may be invisible in this image, but their mass forms a gravitational lens, distorting images of farther galaxies into smears of light.

Bubble-Blowing Black Holes

Those supermassive black holes drive powerful jets of matter that can be larger than the galaxies themselves. The jets carve out bubbles in the material between galaxies, known as the intercluster medium (ICM). These bubbles show up as cavities in the surrounding X-ray-emitting gas, ringed by a bright boundary where the plasma is compressed. The black hole bubbles can throttle the formation of new stars in the galaxies by altering the temperature and density of the gas throughout the cluster.

Additionally, black hole “winds” push some of the interstellar gas in cluster galaxies into the ICM. While most of the ICM is hydrogen and helium plasma, interstellar gas contains relatively high amounts of heavier elements like oxygen and carbon, produced by the galaxies’ stars. In that way, the black holes change the chemical composition of the ICM. The properties of the hot gas are therefore very important for understanding the complex interaction between black holes, intergalactic plasma, and star formation inside galaxy clusters.

Holes in the Ancient Universe

When light from the cosmic microwave background (CMB) passes through a galaxy cluster, it picks up some of the energy from the electrons in the hot plasma, like two pool balls colliding. The extra energy in the light means it disappears from the CMB, so a galaxy cluster looks like a “hole”. This property of galaxy clusters is called the Sunyaev-Zel’dovich effect, and it helps astronomers find galaxy clusters even if they’re too far or faint to be seen easily by the light they emit. Observations of the Sunyaev-Zel’dovich effect help astronomers map out the large scale structure of the universe: the cosmic web made up by galaxies, clusters, and other matter.

- Why do galaxies differ so much in size, shape, composition and activity?

- Why do we need an extremely large telescope like the Giant Magellan Telescope?

Related News

New Theory May Explain Mysterious “Little Red Dots” in the Early Universe

CfA Celebrates 25 Years with the Chandra X-ray Observatory

Black Hole Fashions Stellar Beads on a String

Christine Jones Forman Elected to National Academy of Sciences

A Massive Galaxy Supercluster in the Early Universe

Predoctoral Fellow Discovers Shock Wave in Merging Galaxy Clusters, Confirms Missing Link

A Galaxy Cluster with Two Pairs of X-Ray Cavities

Active Galactic Nuclei and Galaxy Cluster Cooling

Astrophysicists Reveal Largest-Ever Suite of Universe Simulations

The Magnetic Field between the Galaxies in a Merging Cluster

Projects

AbacusSummit

AstroAI

Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI)

GMACS

For Scientists

Telescopes and Instruments

Arcus

See Arcus Website

Chandra

Visit the Chandra Website

Einstein Observatory

South Pole Telescope, Antarctica

Visit the South Pole Telescope, Antarctica Website